Intro to POTA

A little known fact about me – I have my FCC Amateur Radio license. On the airwaves, I am known better as KC3LTS, my randomly assigned call sign. And yes, I wish I had randomly been two more spots down the list so I could have “LTU” as my call sign, I honor of my college.

Ham Radio

Amateur Radio, most commonly recognized as Ham Radio, is something I first learned about as a young Boy Scout but wasn’t something I was keen to get into then. A few years ago, I met a gentleman at a local park who was operating his radio gear from a picnic bench. At the time, I didn’t think much of the interaction, but it left an impression with me and shortly after, I found myself watching YouTube videos about getting your license and operating your radio. It took me a while to sign up for a class and get my license, starting as a Technician class radio operator. This allowed me to get onto the local repeaters and talk to people somewhat nearby but didn’t really scratch the itch. To be fair, I almost walked away from amateur radio.

Then I came across a video where an operator named Mike (call sign K8MRD) was using his radio gear in a state park under the program of Parks on the Air, also called POTA for short. I was captivated and watched every video in his feed. This was the spark that ignited the fire, prompting me to upgrade to the General class radio operator license in order to gain access to the high frequency (HF) range. I immediately signed up for POTA, waited for Santa to bring me an antenna, found a good sale on a great radio, and immediately began activating parks within the system.

Parks on the Air

Parks on the Air started in 2016 as an Amateur Radio Relay League (ARRL.org) Program called National Parks on the Air (NPOTA), designed to encourage people into the national parks while simultaneously giving amateur radio a broader exposure to the public. The program was highly successful, and once the one-year program ended, the Parks on the Air program was born in the wake of the National program. It occurs to me as I am typing this that the gentleman who caught my attention in the park may very well have been operating with National Parks on the Air… hmm, interesting thought.

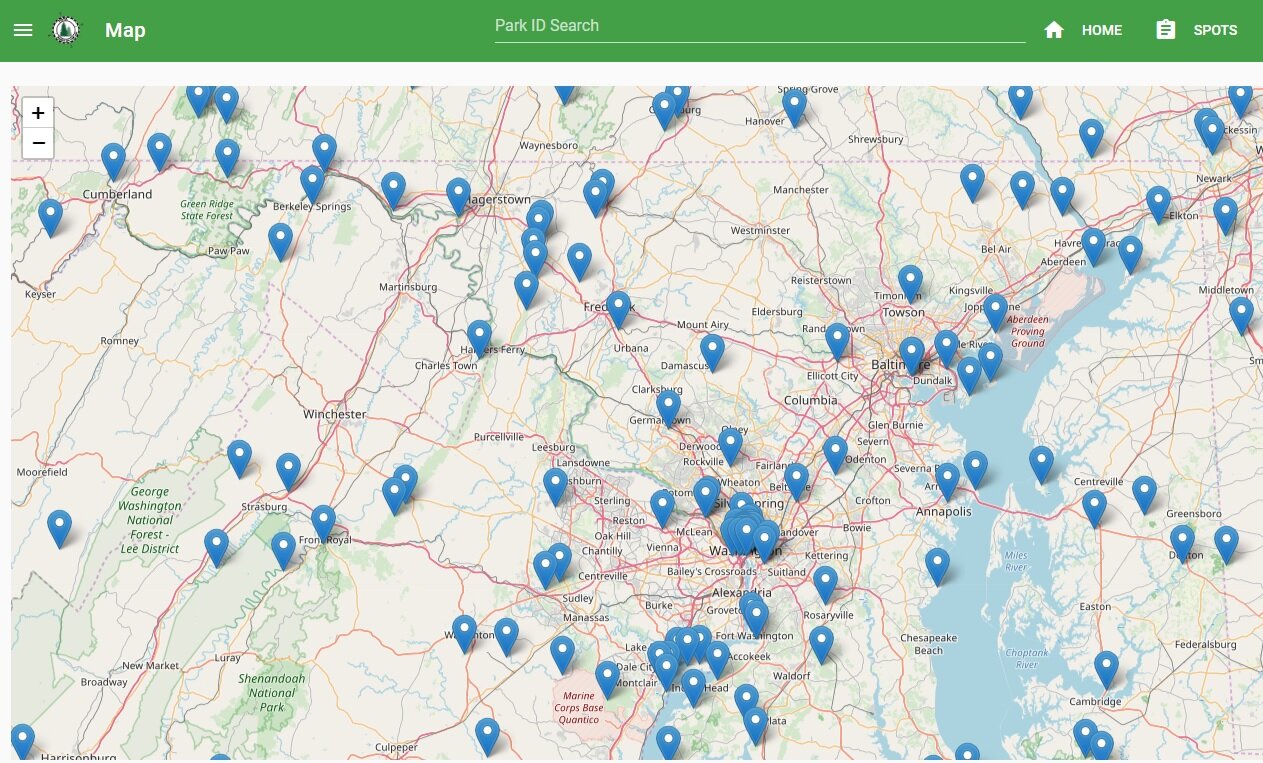

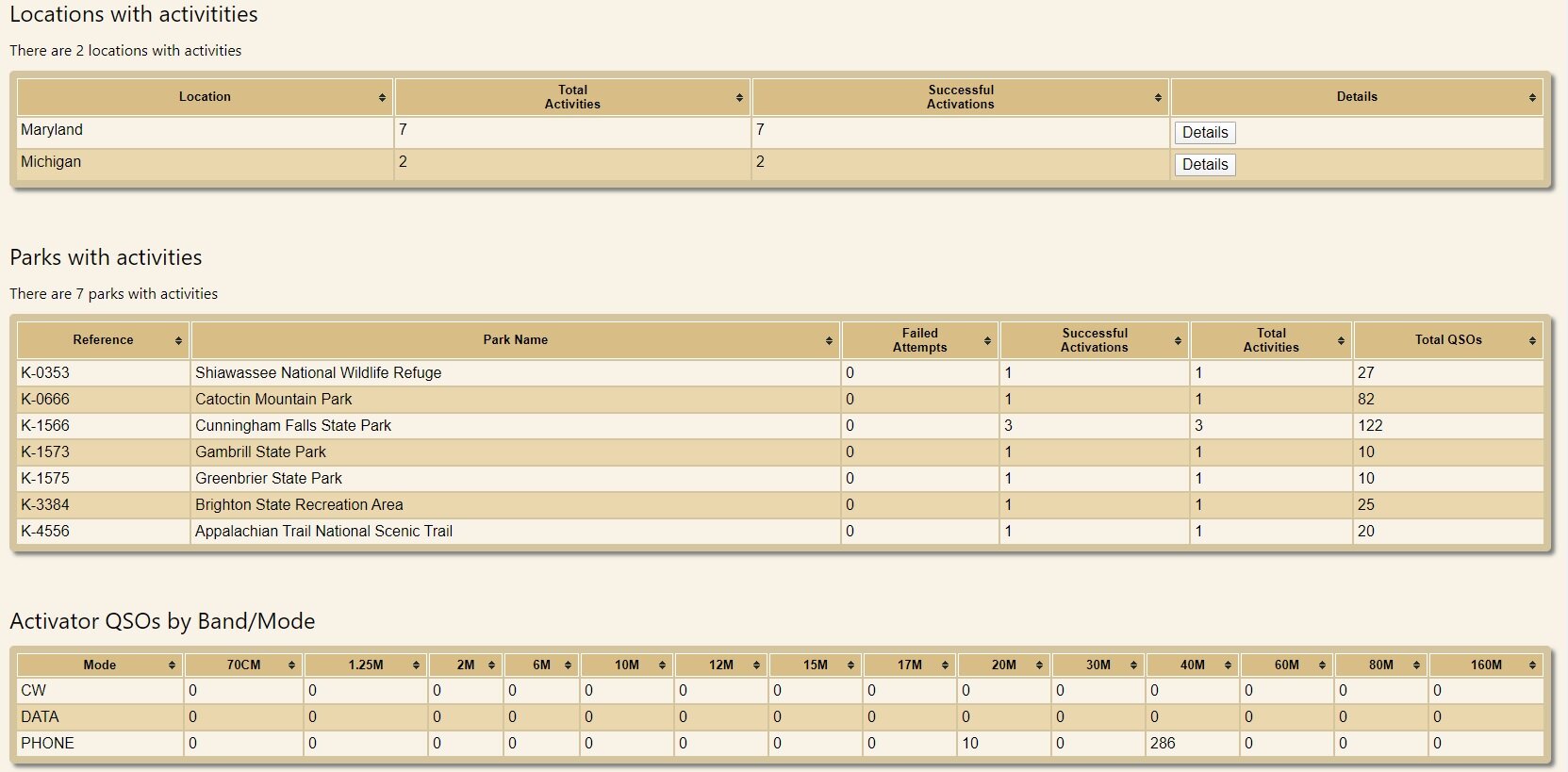

The principle of POTA is simple – activators go to a state or national park entity, which have all been pre-approved through the POTA system and assigned a designation number. All the parks can be found on the POTA Map. Once there, they set up their radio gear. They can operate from the tailgate of their truck, or backpack their gear into a remote location, so long as they are within the park boundaries. Hunters are radio operators who are listening for the activators, whether from home or from another park (called a Park to Park contact), trying to collect as many parks from across the country (and around the world!). POTA has a system in place for announcing where activators are and on what frequencies, along with a Facebook page and Slack channel for social interactions, which has encouraged a friendly community to develop, offering assistance and support to each other. There’s even an informal awards system in place to keep it entertaining (and slightly competitive, although always “friendly competition”). Once activators have packed up and gone home, it’s their responsibility to submit their log to the Parks on the Air regional coordinators in order for the contacts to be input into the system. In order to obtain credit for their contacts, but Hunters and Activators must register for a free account through the POTA website. Once logged on, the website offers a slew of data points for review, which I am sure anyone who read my post on “a Year of eBird” will know I enjoy!

The Rules

There are a few easy rules (https://parksontheair.com/rules/ ) to Parks on the Air, in keeping with the spirit of the game.

Activators must have all equipment on the park property (or within 100 feet of a trail or river entity, such as the Appalachian Trail)

Activators can only activate one reference at a time, even if their location technically sits on more than one, such as the Appalachian Trail crossing through Caledonia State Park. (However, I have also learned that an activator can operate from the two parks consecutively, but not simultaneously, meaning you use one park designation for a while, then take a short break, and start the second park independently of the first, even though you didn’t move locations.)

Activation requires a minimum of 10 contacts (QSOs) within a single day in Zulu Time. If the activator does not obtain the 10 contacts, the hunters can still get credit for their park contacts.

Land repeaters are not allowed, although satellites are permitted.

It really is that simple. The whole program is centered on having fun, getting into the great outdoors, and enjoy nature and amateur radio at the same time.

I realize I am being very simple in my explanation, and for a reason – there are TONS of other blog posts and YouTube videos explaining it far better than I can, so why reinvent the wheel? If you have any specific questions, please feel free to contact me and I will address your questions directly.

Be on the lookout for some more trip reports as I activate more parks this season. Spoiler – I may even start up the Spin The Compass YouTube channel and show you directly what an activation looks like.

Until next time, remember to always Spin the Compass.

73 (old telegraph code for “best regards”)

Jason – KC3LTS